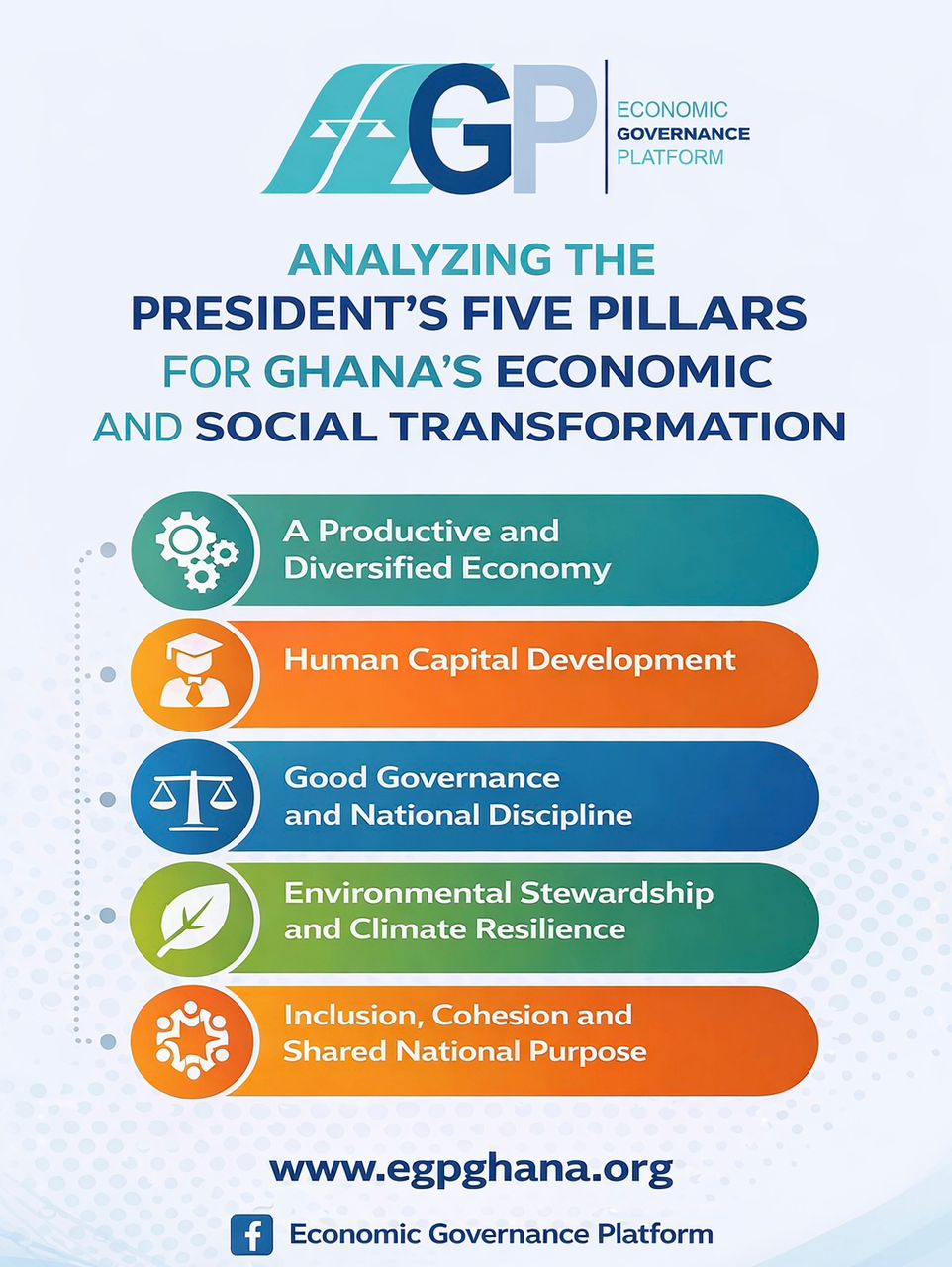

This assessment examines the President’s Five Pillars as a strategic framework for Ghana’s economic and social transformation as reported by the Daily Graphic, with the aim of evaluating their feasibility, coherence, and potential impact. It seeks to move beyond broad policy statements by grounding the pillars in empirical evidence, current economic realities, and institutional capacity.

The assessment draws on credible national and international data to analyze how each pillar aligns with Ghana’s development challenges, including fiscal constraints, unemployment, human capital gaps, governance weaknesses, environmental pressures, and social inclusion. It evaluates both the opportunities presented by the pillars and the structural bottlenecks that could limit effective implementation.

1. 𝐀 𝐏𝐫𝐨𝐝𝐮𝐜𝐭𝐢𝐯𝐞 𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝐃𝐢𝐯𝐞𝐫𝐬𝐢𝐟𝐢𝐞𝐝 𝐄𝐜𝐨𝐧𝐨𝐦𝐲

Ghana’s economic structure remains highly concentrated, making diversification an urgent necessity. According to the Ghana Statistical Service (GSS), agriculture, industry, and services contributed 21.3%, 32.4%, and 46.3% to GDP respectively in 2024, yet exports remain dominated by gold, cocoa, and oil, which together account for over 80% of export earnings. Manufacturing contributes less than 11% of GDP, well below the levels observed in peer emerging economies.

Productivity growth is also weak; the World Bank estimates Ghana’s labour productivity growth at below 1.5% annually over the past decade. This constrains job creation despite positive GDP growth. Achieving this pillar therefore requires scaling industrial value addition, lowering energy and credit costs, and expanding SME access to finance particularly long-term capital if diversification is to translate into resilience and employment.

2. 𝐇𝐮𝐦𝐚𝐧 𝐂𝐚𝐩𝐢𝐭𝐚𝐥 𝐃𝐞𝐯𝐞𝐥𝐨𝐩𝐦𝐞𝐧𝐭

Human capital outcomes in Ghana reveal a strong access–quality gap. While Free SHS has raised secondary school enrolment by over 30% since 2017, learning outcomes remain weak. The World Bank’s Human Capital Index (2023) places Ghana at 0.44, meaning a child born today will be only 44% as productive as they could be with full education and health.

Unemployment among youth (15–35 years) stands at over 19%, with underemployment significantly higher, reflecting persistent skills mismatch. In health, Ghana spends about 3.2% of GDP, below the Abuja target of 15% of government expenditure, contributing to NHIS arrears and health worker emigration. Without stronger investment in TVET, skills alignment, and health system financing, the human capital pillar risks yielding limited economic returns.

3. 𝐆𝐨𝐨𝐝 𝐆𝐨𝐯𝐞𝐫𝐧𝐚𝐧𝐜𝐞 𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝐍𝐚𝐭𝐢𝐨𝐧𝐚𝐥 𝐃𝐢𝐬𝐜𝐢𝐩𝐥𝐢𝐧𝐞

Governance weaknesses have been a central driver of Ghana’s fiscal distress. Public debt rose from 55% of GDP in 2019 to over 90% in 2023, prompting IMF intervention. The IMF Governance Diagnostic Assessment (2024) highlights vulnerabilities in procurement, SOE oversight, and asset declaration enforcement.

Corruption-related inefficiencies are estimated by Transparency International and UNDP to cost Ghana 2–3% of GDP annually, equivalent to several billion cedis in lost public resources. While institutions such as the Auditor-General and OSP exist, enforcement remains uneven. This pillar can only be realized if fiscal rules are respected beyond IMF conditionality, procurement transparency is strengthened, and accountability institutions are insulated from political influence.

4. 𝐄𝐧𝐯𝐢𝐫𝐨𝐧𝐦𝐞𝐧𝐭𝐚𝐥 𝐒𝐭𝐞𝐰𝐚𝐫𝐝𝐬𝐡𝐢𝐩 𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝐂𝐥𝐢𝐦𝐚𝐭𝐞 𝐑𝐞𝐬𝐢𝐥𝐢𝐞𝐧𝐜𝐞

Environmental degradation poses direct economic risks. Illegal mining has polluted over 60% of Ghana’s major water bodies, according to the Water Resources Commission, raising water treatment costs and threatening public health. Climate shocks also affect food prices: the World Food Programme estimates climate-related disruptions could reduce agricultural output by up to 10% by 2030 if adaptation is weak.

Despite commitments to renewable energy, Ghana’s energy mix remains over 60% thermal, increasing fiscal and exchange rate pressures through fuel imports. Achieving this pillar requires credible enforcement against environmental crime, climate-smart agriculture, and scaled investment in renewables to reduce long-term economic vulnerability.

5. 𝐈𝐧𝐜𝐥𝐮𝐬𝐢𝐨𝐧, 𝐂𝐨𝐡𝐞𝐬𝐢𝐨𝐧, 𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝐒𝐡𝐚𝐫𝐞𝐝 𝐍𝐚𝐭𝐢𝐨𝐧𝐚𝐥 𝐏𝐮𝐫𝐩𝐨𝐬𝐞

Growth in Ghana has not translated into sufficient inclusion. The Gini coefficient remains above 0.43, reflecting persistent inequality, while poverty rates in northern regions are more than double those in Greater Accra. Youth unemployment and informality, where over 80% of workers are engaged continue to undermine social cohesion.

Although social protection programmes exist, coverage and adequacy remain limited due to fiscal constraints. The IMF notes that social spending efficiency, not just spending levels, is critical. Without targeted job creation, regional equity, and credible opportunity pathways for young people, inclusion risks remaining aspirational rather than transformational.

𝐂𝐨𝐧𝐜𝐥𝐮𝐬𝐢𝐨𝐧

The President’s Five Pillars articulate a sound and internally consistent development vision, but Ghana’s data clearly show that success depends on deep structural reforms, sustained fiscal discipline, and implementation credibility. The pillars are achievable, but only if backed by productivity-enhancing investments, human capital quality improvements, governance enforcement, climate resilience financing, and inclusive growth strategies that go beyond headline policies.

References

Bank of Ghana (BoG). (2024–2025). Monetary Policy Reports. Accra: Bank of Ghana.

Available at: https://www.bog.gov.gh/publications/monetary-policy-reports/

Bank of Ghana (BoG). (2024). Annual Report. Accra: Bank of Ghana.

Available at: https://www.bog.gov.gh/publications/annual-reports/

Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), Ghana. (2023). State of the Environment Report. Accra: EPA.

Available at: https://epa.gov.gh/epa/publications.php

Energy Commission of Ghana. (2024). National Energy Statistics and Outlook. Accra: Energy Commission.

Available at: https://www.energycom.gov.gh/index.php/data-center

Ghana Statistical Service (GSS). (2024). Gross Domestic Product (GDP) – Annual & Quarterly National Accounts. Accra: GSS.

Available at: https://statsghana.gov.gh/gdp.php

Ghana Statistical Service (GSS). (2024). Labour Force Survey Report. Accra: GSS.

Available at: https://statsghana.gov.gh/labourforce.php

International Energy Agency (IEA). (2024). Ghana Energy Profile. Paris: IEA.

Available at: https://www.iea.org/countries/ghana

International Labour Organization (ILO). (2024). Employment and Informality Statistics – Ghana. Geneva: ILO.

Available at: https://www.ilo.org/africa/countries-covered/ghana

International Monetary Fund (IMF). (2023). Request for an Extended Credit Facility Arrangement—Ghana. Washington, DC: IMF.

Available at: https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/CR/Issues/2023/05/03/Ghana-Request-for-an-Extended-Credit-Facility-Arrangement-532822

International Monetary Fund (IMF). (2024). Ghana: Fifth Review under the Extended Credit Facility Arrangement. Washington, DC: IMF.

Available at: https://www.imf.org/en/Countries/GHA

International Monetary Fund (IMF). (2024). Ghana Governance Diagnostic Assessment. Washington, DC: IMF.

Available at: https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/CR/Issues

Ministry of Finance (MoF), Ghana. (2024). Public Debt Statistical Bulletin. Accra: MoF.

Available at: https://mofep.gov.gh/publications

Ministry of Gender, Children and Social Protection (MoGCSP). (2024). LEAP and Social Protection Programme Reports. Accra: MoGCSP.

Available at: https://www.mogcsp.gov.gh

Ministry of Health (MoH), Ghana. (2024). Holistic Assessment of the Health Sector Programme of Work. Accra: MoH.

Available at: https://www.moh.gov.gh

Transparency International. (2024). Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI). Berlin: Transparency International.

Available at: https://www.transparency.org/en/cpi

World Bank. (2024). Ghana Country Economic Update. Washington, DC: World Bank.

Available at: https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/ghana/publication

World Bank. (2023). Human Capital Index – Ghana. Washington, DC: World Bank.

Available at: https://www.worldbank.org/en/publication/human-capital

World Bank. (2024). World Development Indicators (WDI): Ghana. Washington, DC: World Bank.

Available at: https://data.worldbank.org/country/ghana

World Health Organization (WHO). (2024). Ghana Country Health Profile. Geneva: WHO.

Available at: https://www.who.int/countries/gha

OXFAM in Ghana Ghana Anti-Corruption Coalition BudgIT Africa Centre for Energy Policy Open Society Foundations International Monetary Fund World Bank Transparency International